Q&A: Dani Sayeau

Dani is a medical illustrator and a graduate of Sheridan College’s Honours Bachelor of Illustration program. They met with us to answer some questions about what it’s like working in the field of medical illustration.

Why did you choose medical illustration?

This is such a non-serious answer for a very serious profession, but way back in first year, I really liked the skeleton drawing unit. I remember thinking, “This is very fun. How do I draw more skeletons?” It spiralled from there. What I liked about drawing skeletons was being able to learn things and deal with really complicated subject matter. It made science feel fun and approachable to me in a way it never had before.

Were there any pivotal moments that led you to your career or that got you started in this field?

I think overall, seeing the value of medical education and particularly the value that patient education materials really have on the people who access them. There are more complex surgical illustrations for medical professionals, but the thing that I think is really important and impactful about this field is making things for patients. For people who may not have high levels of health literacy and who are going through something really scary, it’s the ability to actually help people with this kind of work. Not that I think making beautiful art doesn’t make the world a better place. It just felt like a really tangible impact.

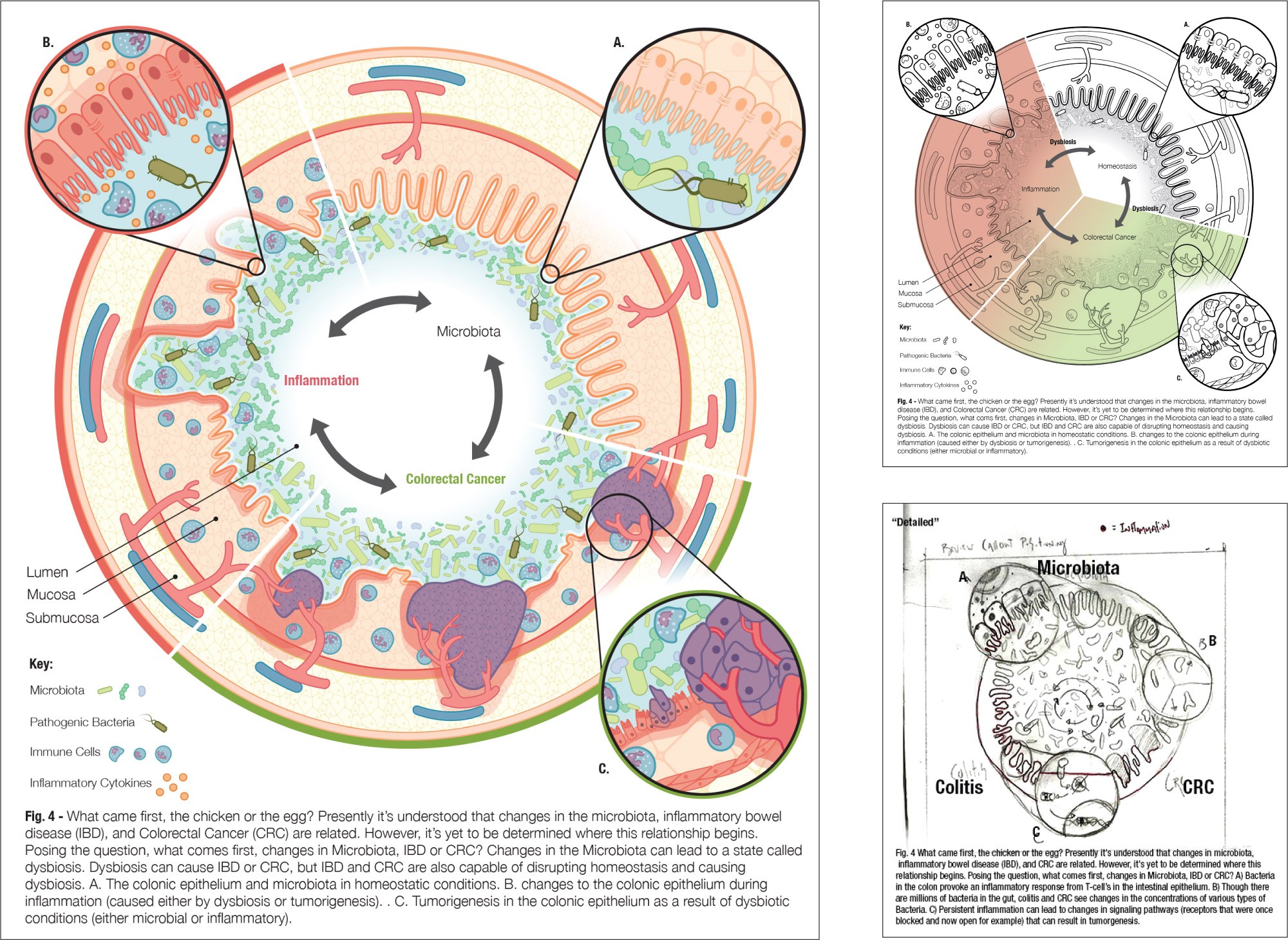

THE MICROBIOME, COLORECTAL CANCER, AND INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Process work (right) and final (left)Have you found that your scientific education has given you an advantage over scientific illustrators who only have an art degree?

It depends on the context of what I’m doing and who I’m doing it for. Most of my medical work these days is surgical illustration, and generally, what that entails is working with a surgeon to describe a technique they are working on for publication in a medical journal. I think that if I hadn’t taken a gross anatomy course and hadn’t gotten really familiar with how the operating room works in my training, it would have been a lot harder to work with them. Especially in illustrating surgery, you have to know the surgery backwards and forwards in order to draw it. So, there’s sort of a requirement there. But I don’t think you need a formal biology degree for that, either. Even taking an anatomy course gives you the skillset to do it. Honestly, as long as you have a baseline level of science literacy, I think it’s pretty easy to just read some papers and pick that stuff up.

It’s helpful to know the technical terms, too. I love surgeons, they’re very good at their work, and they’re very busy saving lives, but they’re also the toughest clients I’ve ever worked with. They are very exacting and want things perfect and will say things like, “Well, I don’t use that kind of Stevens, so you’ve drawn this wrong.” You have to take very meticulous notes about everything they use, and even the way they tie off an incision is important to them.

Are there any pros and cons of being a medical illustrator compared to other illustration jobs?

This could be a pro and a con depending on your personality, but there’s a lot of research. I actually love research; it’s my favourite part of every job, and I get a little bored when I have to finish a drawing. For me, it’s great because I get to learn new things, and they’re always really complicated things, but I have colleagues who are more like, “I just want to make beautiful pictures. Why do I have to do this?”

The other con is that not a lot of people know about us. There’s a lot of time explaining what you do. Surgeons and the people who make up your client base when you work freelance tend to know us. But molecular biologists or other kinds of immunological researchers are often less familiar with us as a discipline when actually they could really use us to help communicate their research. There is a lot of getting your foot in the door, and it’s not just an elevator pitch about your work. It’s more like, “This is what we do, and I kind of have to sell you on the principle of this field.”

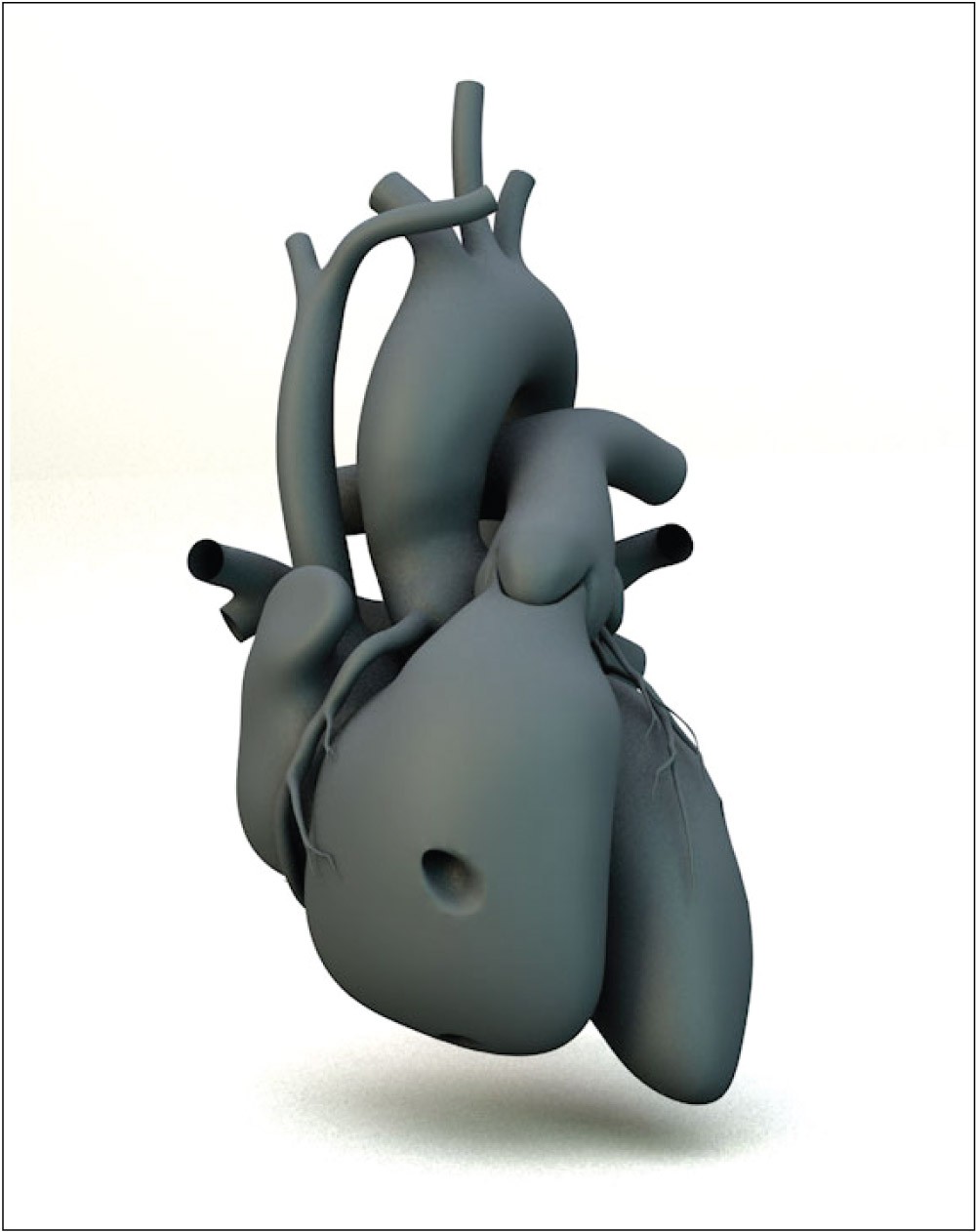

MODELING THE HUMAN HEART

Lumen model

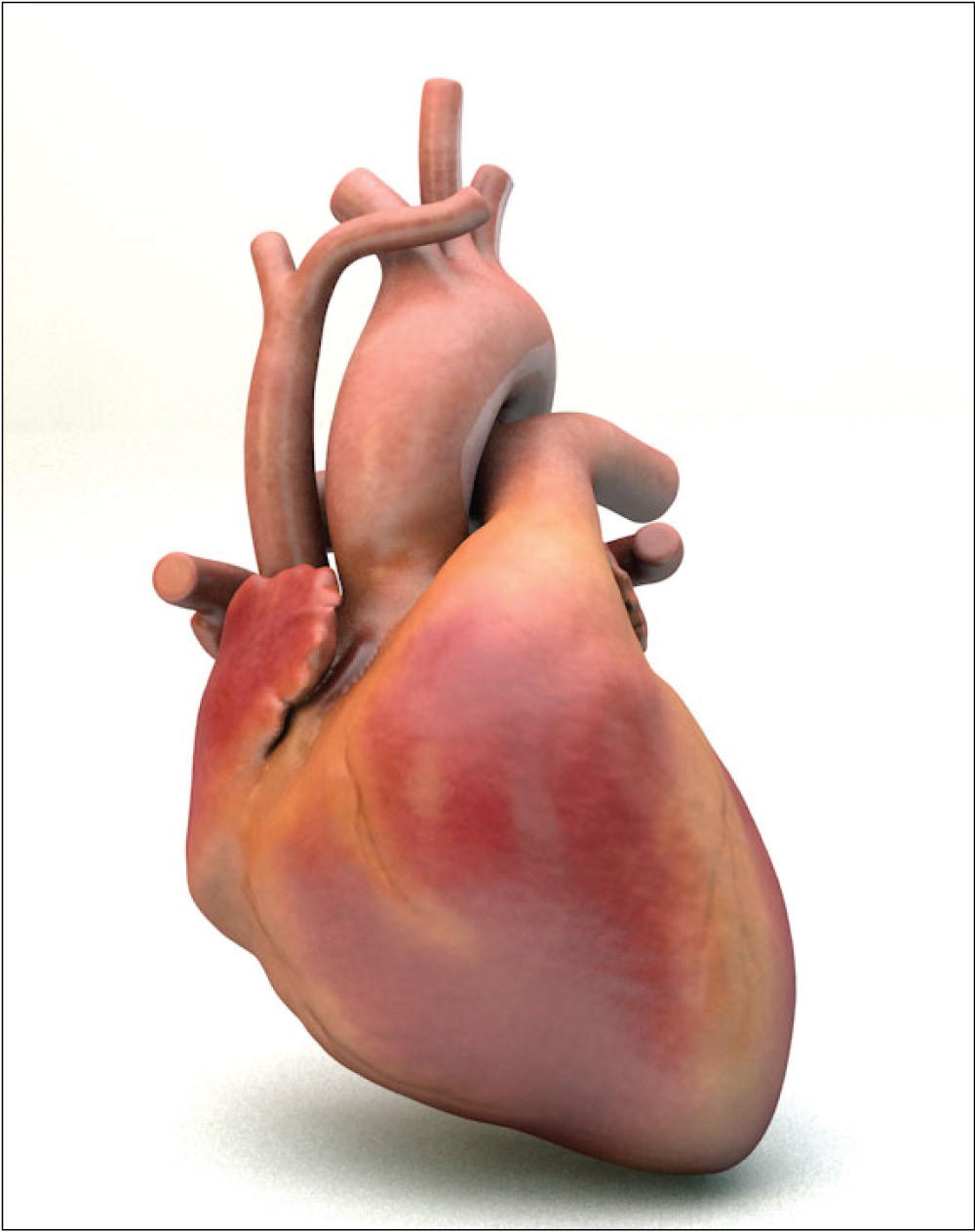

MODELING THE HUMAN HEART

Final surface model

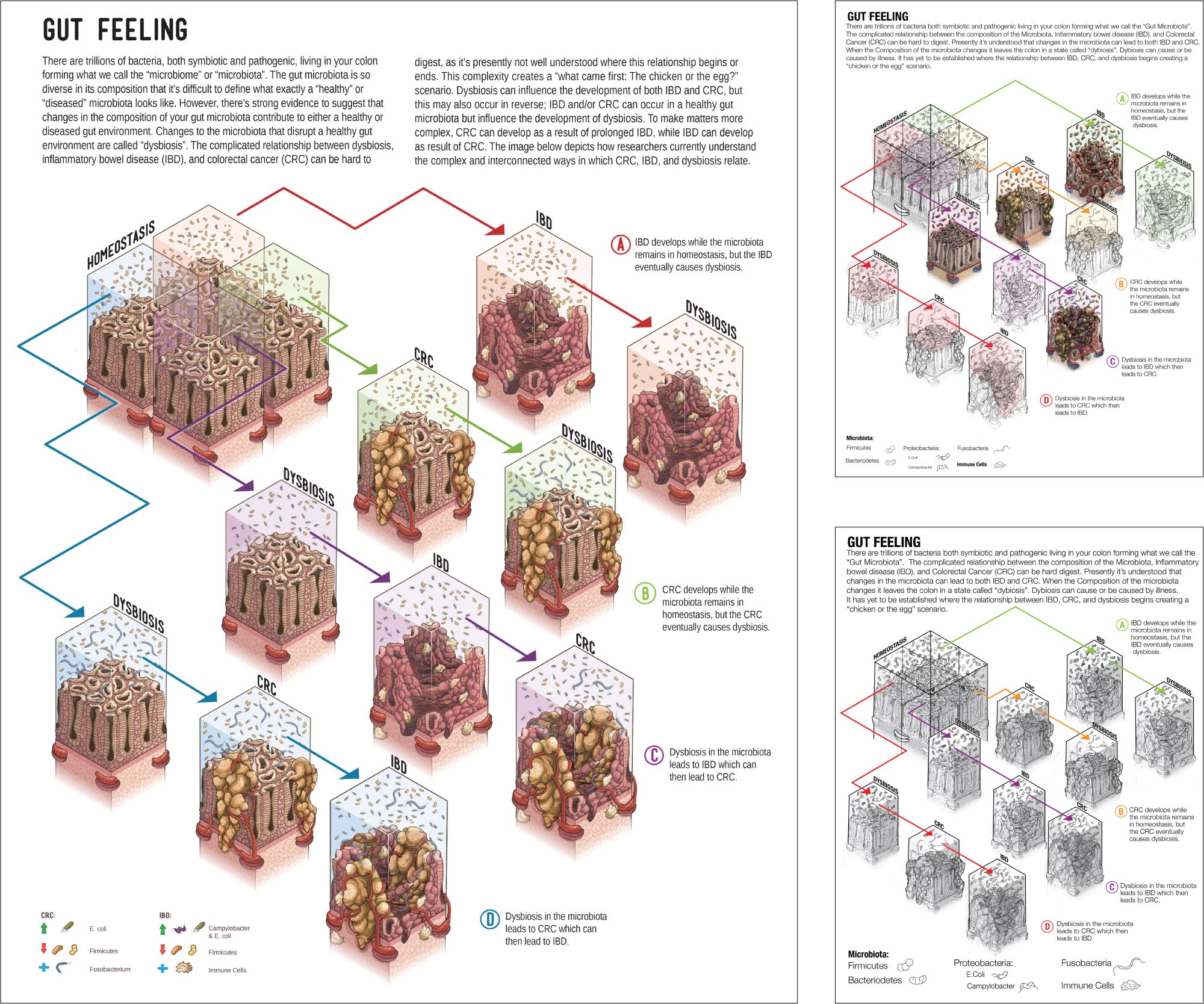

GUT FEELING

Demonstrating the complex and interconnected relationship between the gut microbiome, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal cancer in an easy to digest, three dimensional representation.

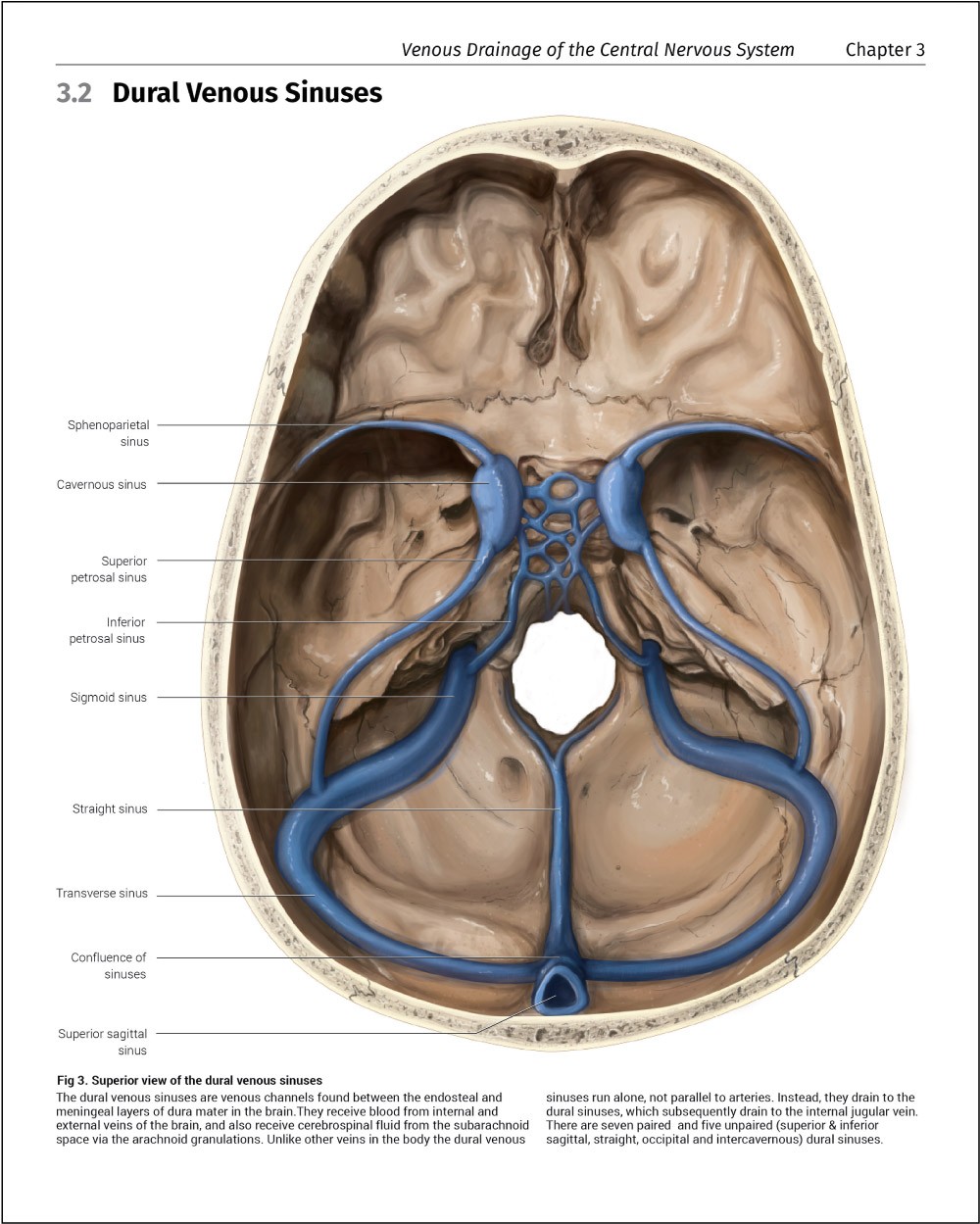

DURAL VENOUS SINUSES

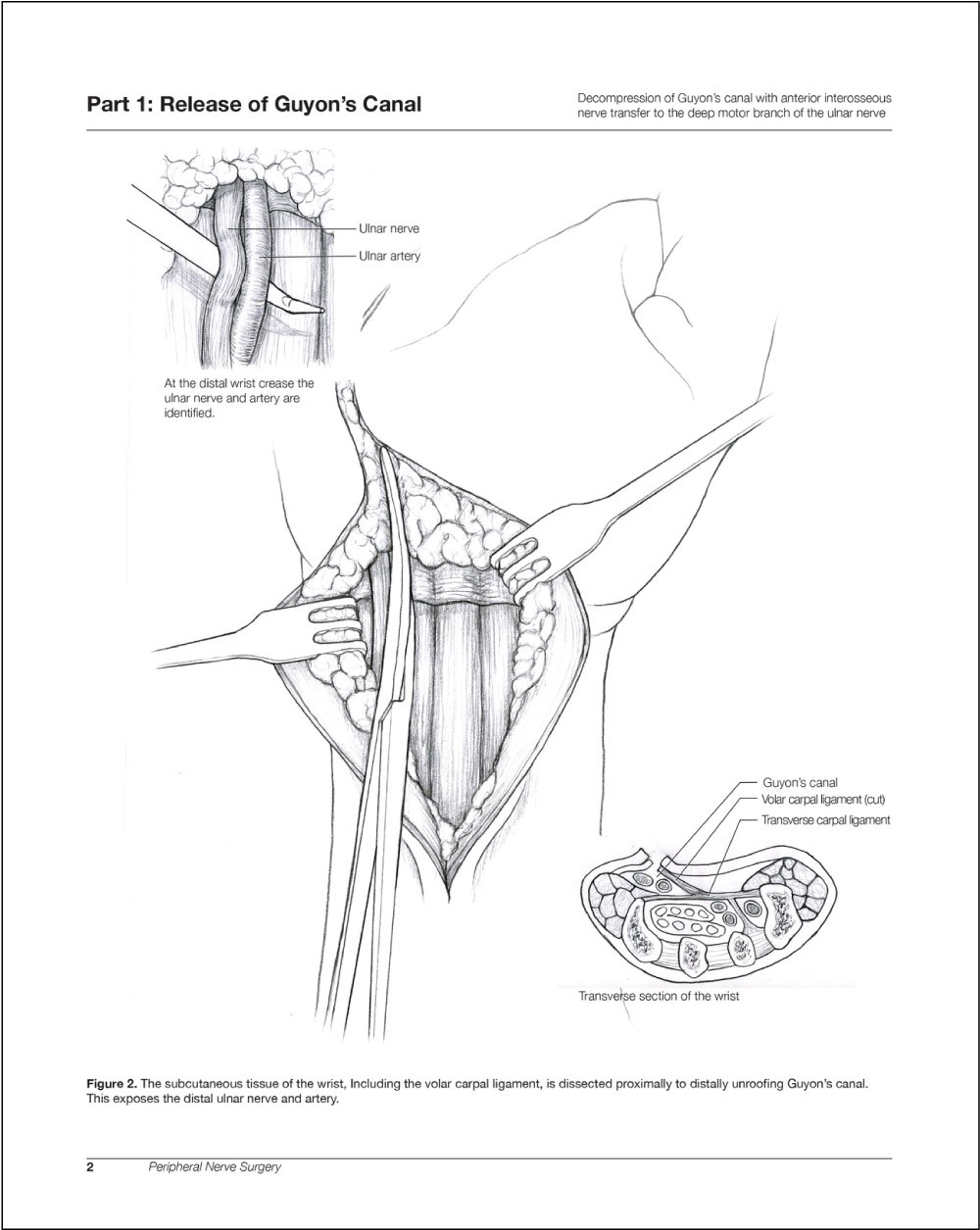

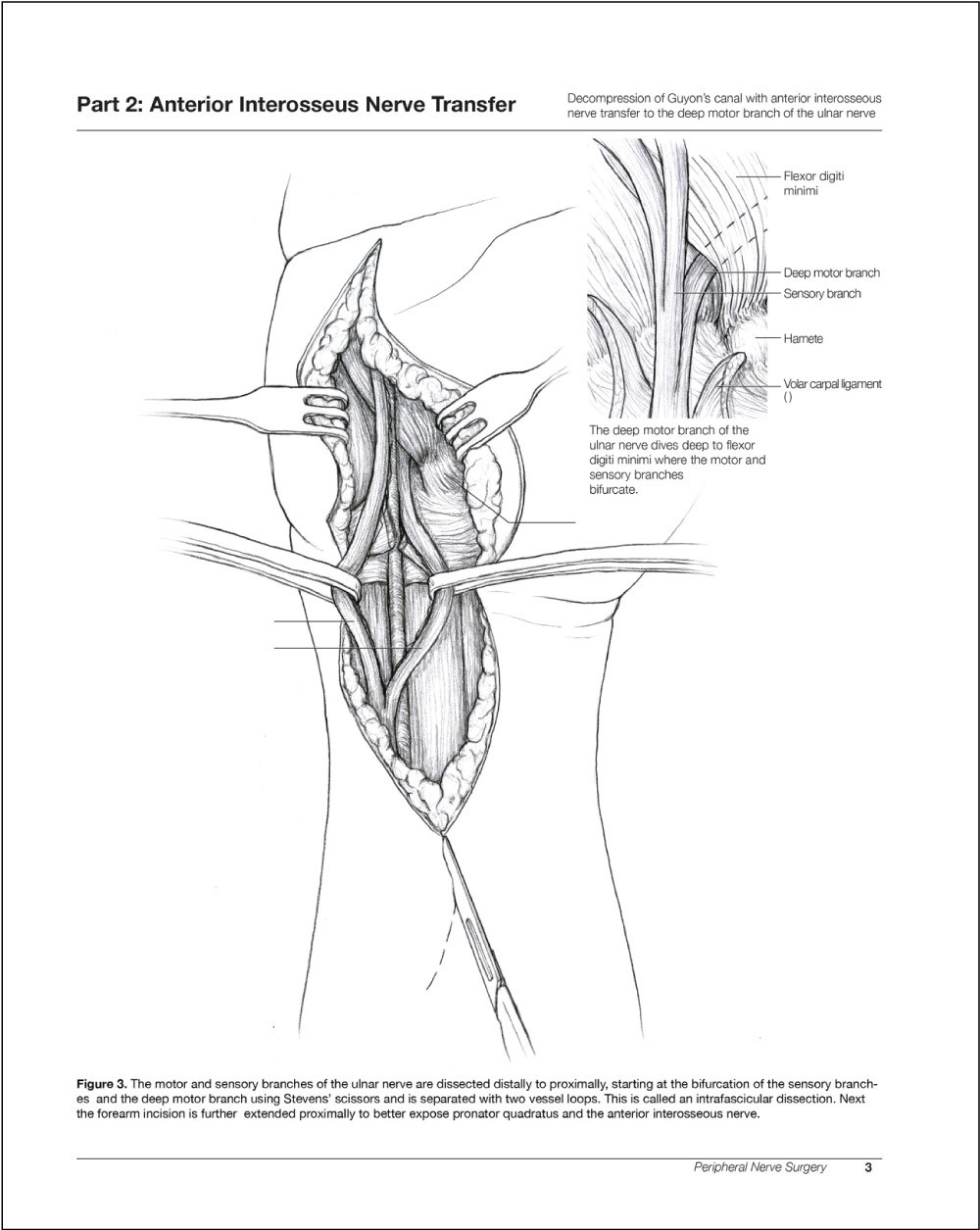

DECOMPRESSION OF GUYON’S CANAL

A sequence of images describing the process of performing an anterior interosseous nerve transfer

DECOMPRESSION OF GUYON’S CANAL

A sequence of images describing the process of performing an anterior interosseous nerve transferCould you share a bit of your creative process?

A lot of the process up front is research. Sometimes if I’m lucky and the timing works out, I get to watch the surgery in the operating room. You’ll do a lot of up-front research about the surgery and what the steps are ahead of time, and you’ll consult with the surgeon about what they’re doing. You’ll go in, watch the surgery happen, frantically take notes, and sketch, too. From there, I tend to write a script of what happens in each step of the process, and I’ll check with the surgeon to see if it’s right. Since generally the purpose of these illustrations is to communicate how to do the surgery to other surgeons, if it’s wrong, it’s a big problem. That’s where I think the anatomical accuracy comes into it, too. Once we’re all happy with it, I’ll start thumbnailing out each major step that gets an illustration.

With a sequential narrative like this, it’s important to maintain context at every step, which means not changing the angle or view as you’re moving through each sequence unless it’s necessary. Part of the work and part of why medical illustration is a lot more valuable than photos, besides the blood, is the ability to orient yourself around the surgical field and the patient. In surgery, they cover everything that’s not the open wound with a blanket, so if you’re trying to understand where in the body you are, that’s difficult.

Once I have the thumbnails done, I’ll do a rough draft where I’m thinking about the anatomy and placing tools in the scene. I have a lot of surgical tools as references. When a piece of equipment is really complex, I’ll actually build it in 3D, then take my illustration as a background image and place the 3D model where I want it to be. I make physical models, too. I’ll do things like use a series of toothpicks and some shoelaces to understand the direction something’s going to pull in. Sometimes when the surgery is really complex, or if a view angle is really complex, or if I have to draw hands, which is often, I’ll put gloves on my own hands and take pictures of them at the angle holding a banana or something as needed to get the perspective right. From there, it’s back and forth with the surgeon again, and we’ll go to a final.

I like to do line work for surgical illustration. It’s faster, it’s cheaper, and you can get a bigger series of illustrations to better tell the story, but sometimes surgeons want highly rendered paintings for every step of the surgery.

What do you feel is the most valuable skill required for medical illustration?

I think it’s really the core skill of being able to communicate complexities. The ability to take something that maybe you just learned about and turn it back into something that you can teach other people. I find I kind of have to become an expert on a surgery, and it will leave my brain a month later, but I have to very quickly get the hang of it.

Sometimes, even having foundational knowledge of something isn’t adequate, so you have to learn the thing really well and really fast. I think that it’s a useful and transferable skill outside of medical illustration, too.

Would you consider your skills in 3D modelling necessary or an asset for this field of illustration?

It depends on what you want to do. I have friends where 3D is their bread and butter and it’s all they do. I love 3D and I think it’s useful as an accelerator, especially with surgical tools, but it’s not really necessary for a lot of the work that I do. I will say that it trains your brain to think about 3D space in a way that is kind of hard to wrap your head around when you’re trying to learn perspective and structural drawing on a 2-dimensional plane. I think a lot of things regarding perspective drawing start to click when you have to work in a 3D space. It’s the thinking behind having to build objects in 3D and arranging a camera to get the viewpoint you want.

To see more of Dani’s work, visit www.danisayeau.com

Interviewed and presented by 2024 grads: Sophia Bos, Yixin Guo, Ven Lavergne, Brynn Mercer, Tetra S.